If you are using Chrome, click the red hand button at the top right of the screen:

Then select: Don't run on pages on this site

If you do it correctly, the red hand will turn to green and you will no longer see this message.

"now could I drink hot blood"

(Shakespeare - Hamlet)

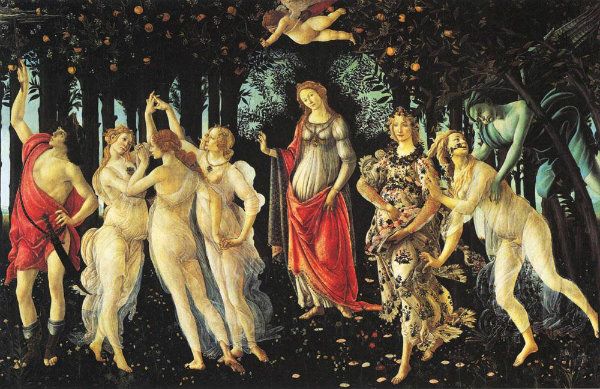

La Primavera: An Analysis

La Primavera is a tempera panel painting by the famous Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli currently housed by the Uffizi Gallery of Florence. This extremely controversial painting, described by Cunningham and Reich, is “one of the most popular paintings in Western art, andis an elaborate mythological allegory of the burgeoning fertility of the world.” Botticelli’s purpose of Primavera, described by Streeter, is purely decorative. The subject is to describe the glories of springtime, and also to express the delightful sylvan life (Streeter, 67). The allegory behind the painting can be interpreted in so many different ways and was never clearly defined, thus creating mysteriousness. The featured nine mythological characters were definitely recognizable: from the far right is the god of wind Zephyrus approaching nymph Chloris, whom transforms into the goddess of flowers, Flora; on the left, is Mercury and the three dancing graces; the central figure is Venus, immediately above her head is a blindfolded Cupid. Nobody knows the exact story of the painting, nor the exact year it was painted. But what can be found, is from the interaction, body gestures, clothing, and key features of these mythical figures, along with the hints within the painting will provide a better interpretation on Botticelli’s allegorical message in La Primavera. This essay is to explore experts’ different interpretations to gain a better understanding of the allegories of La Primavera.

D’ancona suggested that the painting was produced around 1482, and was commissioned for a member of the Medici Family, a powerful political and banking house in Florence around the fourteenth century. In 1482, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, the cousin of Lorenzo the Magnificent, signed the wedding contract to Semiramide Appiani, the sister of Jacopo IV, Lord of the Island of Elba and of Piombino. It was believed that Botticelli was commissioned to paint the Primavera for Lorenzo’s wedding. Primavera was part of a decoration in Pierfrancesco’s house in Florence, where it was hung or fixed above a lettuccio, which is a kind of settle that stood and fixed against the wall in the chamber next to Lorenzo’s bedroom (Lightbown, 122). D’Ancona furthermore supported this phenomenon by stating that the paining was framed in a white frame, which white is a proper color for weddings. Moreover, Venus represented love, which would be even more suitable if the painting was meant for a wedding decoration (Lightbown, 122).

Primavera consists of nine mythical figures. The figures are composed into two groups of three plus three single figures (D’ancona, 33). The setting consists of plants such as a semicircular meadow, deep-spread with green grasses and flowering plants on the background: coltsfoot, forget-me-nots, cornflowers, periwinkles, daisies…etc. This garden is the garden of Venus, imagined by Botticelli as the Garden of Hesperides, a blissful garden that lays in the far west in classical greek myths. The flowers and orange trees provides evidence that the season is spring (Lightbown, 74).

Venus in the middle lifts up her hand while walking towards her right. Venus’ position in the center singles her out and signifies that she is the most important figure in this picture. Richly attired, well representing the goddess of love and marriage. Venus stands with her belly leaning forward, wearing a loose white robe and puffy sleeves. Around her neck is a gold chain with pearls. A cloak draped over her right arm and in front of and down her body. She wears a white headdress with transparent veil, which is a headdress of a married woman in the fifteenth century. Venus, gestures her hand towards the Graces, directs spectator’s attention towards the interaction between Cupid and the Graces (Lightbown, 75).

On the far right, the violent greenish-blue winged figure comes crashing through the laurel trees, is identified as Zephyrus, the god of west wind, and the bringer of spring breeze. Jacobsen questions this figure’s identity as Zephyrus. He claims that the winged figure looks a lot different than the Zephyrus in Botticelli’s other painting The Birth of Venus. Plus his violent appearance contradicts his mild character as the bringer of the light spring breeze. The green color of this figure, as described by Jacobsen in D’Ancona’s book, is a symbol of death and decay, which he identifies such figure as the Angel of death trying to take a soul back to the underworld. His theory is now discredited because after the cleaning, the figure of Zephyrus turned out to be blue. The figure of Zephyrus’ blue-green appearance, described by D’Ancona, is the result that he is born out of the sea. Furthermore, the connotation of death in Italy is usually presented as a skeleton or as black. Zephyrus in this case, has puffed cheeks blowing out wind, which is a usual attribute of a wind god (D’Ancona, 35).

Described in Ovid’s Fasti, a poetical calendar of the Roman year, Zephyrusflies down through the laurel trees and seizes the nymph Chloris, who she comes running barefoot and terrified. Zephyrus was possessed by the beauty of nymph Chloris, and could not control his actions. Such possession on Chloris created the impulse to rape the nymph. In Ovid’s Fasti, Chlorisexplains the story about how she got raped by the Western Wind, then later he promised her a marriage, and transferred her into Flora, the goddess of flowers. As Chloris speaks, she blows roses from her mouth. However, Botticelli has modified the motif by depicting several flowers – violets, strawberries, periwinkles and cornflowers that issuing from the nymph’s mouth, altogether with the roses mentioned by Ovid. (D’Ancona, 36). After the transformation into Flora, she enjoys perpetual spring, when the trees, grass, and flowers are the freshest of all seasons. “She was gleaming white, and shining white as her dress. Though painted with roses and flowers and greenery, the unbound hair of her golden head, falls over the brow that is humbly proud… and her lap filled with flowers.” (Myths or Fingerprints?, video). Her dress covered in flowers, crowned with flowers, and scattering roses as she walks.

Immediately above Venus’ head, is the golden haired, blindfolded Cupid shooting a flaming torch towards one of the Graces. There has been two different sayings about Cupid’s aim of the flaming torch towards the Graces; Lighbown states that the arrow is pointing towards the first Grace on the left, but D’Ancona describes that the Cupid’s arrow is aimed towards the middle grace whose back is turned against the spectators. It makes more sense when the arrow is pointed towards the middle Grace, because the middle Grace is the one who glazes at Mercury in the left, inflamed by the flaming torch aimed by Cupid (D’ancona, 54).

Lightbown described the Graces as following: “Their beauty is of sort admired… a form white and tall, but not too thin, well-shaped heads, long and elegant hands, an elegant but not too slender neck, an oval face, thick blond tresses, a lofty port.” (Lightbown, 75). The Graces’ fingers are locked-in performing a circular dance. Many critics has claimed that they are sisters because they seem much alike (Lightbown, 75). The source for Botticelli’s Graces is founded in Alberti’s description of the Graces in his passage De Pictura: “There are moreover those three youthful sisters to whom Hesiod assigned the names Aglaia, Euphrosyne, and Thalia…painted with hands interlocked, smiling, and clad in loosened and transparent garb.” (Ibid, 103). Botticelli based his interpretation off of Alberti’s lead of the representation of the three sisters (Dempsy 1971, 327). In Alberti’s famous passage, he also revealed that the motifs of the Grace’s flowing hair and the exquisite effect of the breeze ruffling their tunics, which Botticelli responded such description in his painting (Lightbown, 77). Panofsky pointed out that the dance between the Graces is meant to be a joyful accompaniment at weddings, which supports D’Ancona’s theory about Primavera as a wedding gift. D’Ancona also interpreted the Three Graces as the representation of the three months of Spring: March, April, and May

Lilian Zirpolo stated that Botticelli’s Graces presents the theme of chastity found in Camilla and the Centaur, which they attributes the chaste behavior. Described by Seneca, the Three Graces, as attendants of Venus, are “pure and undefiled and hole in the eyes of all.” Zirpolo furthermore explained that The pearl accessory on the right Grace’s head, along with the pearl necklace represents her purity. Cupid’s aim at one of the graces meant that she is about to abandon her virginity for marriage. (Zirpolo, 25). Zirpolo’s theory contradicts with D’Ancona’s theory about the Grace’s marital status. According to D’Ancona, two of the three Graces were married, while the remaining Thalia is still unmarried. The Graces represented as Beauty, Chastity, and Seduction from left to right respectively. Botticelli identifies Chastity as the bride, which follows the long lasting tradition that the bride should come to her wedding as a virgin. And it is thereby, Cupid, who is the one who inflames Thalia’s love towards Mercury on the left (D’Ancona, 55).

On the far left, Mercury stands facing outwards, turning his back on other figures, weight resting on his left leg, his sward hangs over his left thigh. He wears a metal helmet, and penetrates a group of clouds with his sacred wand. His position and gesture has puzzled many scholars. D’ancona explained this phenomenon by explaining that Mercury is usually identified by his leather helmet, or by his hat (the petasus), and in addition to his winged boots, and the sacred wand with snakes (D’Ancona, 52). To understand the allegory of Mercury, Dempsy interpreted that the Primavera is based on the rustic farmer’s calender. The central figure Venus is the domain of the spring season’s setting. The whole season unfolds in the painting, beginning from Zephyr from the right, continuing through Venus whom represents April, ending in May which is Mercury on the left. Also supported by Ovid, the origin of the name for the month of May has been closely related to the name Mercury. This explains why Mercury has his back turned to the rest of the group because his month, May, is the last month of spring, and is the beginning of summer, which is the direction he faces in the painting (Dempsy 1968, 264). Mercury is shown dispelling a group of cloud from the sky with his sacred wand, or his caduceus. This action, according to Dempsy, is a result to complement Zephyr’s hasty entrance into the scene.

Dempsy also argued thatthe group on the right side of Primavera including Zephyrus, Chloris, Flora, Cupid and Venus, is referenced from Lucretius’s passage De Rerum Natura: “On come Spring and Venus, and Venus’s winged harbinger [Cupid] marching before, with Zephyr and mother Flora a pace behind him strewing the whole path in front with brilliant colors and filling it with scents.” (Lucretius, 737). The left half of the Primavera, including Venus and Cupid again, along with the Graces, and Mercury is based on Horace’s Odes: “O Venus…forsake thy beloved…and with three let hasten thy ardent child; the Graces too, with girdles all unloosed, the Nymphs, and Youth unlovely without thee, and Mercury!” (Horace, 30). Botticelli altered the emphasis of Lucretius’s description of transitioning into Ovid’s account in Fasti on Flora’s metamorphosis into the growing process of spring. Such process was completed by the representation of the figure Venus (Dempsy 1968, 260).

D’acona states that only the right side of Primavera is derived from Ovid’s Fasti, while the left side is loosely based on Poliziano’s Stanze. The close relationship between Botticelli’s painting and Poliziano’s Stanze per la Giostra del Magnifico Giuliano di Piero dei Medici as described: “She is white, and her dress is white, but decorated with roses and flowers and grass; her curly blond hair falls down from her head onto her brow, which is humblr proud. The entire wood around her is smiling…every Grace finds enjoyment, where Zephry flies behind Flora and covers the green meadow with flowers…The joyful Spring is never absent, with her windswept curly blond hair, she weaves counless flowers into a garland…”. D’ancona believes that there is a close similarity between both Poliziano’s Stanze and Ovid’s Fasti, therefore, suggests that Botticelli has based his Primavera on both poems (D’ancona, 41).

With its origins as mysterious as ever, uncovering the real meaning of Primavera, has proved to be a challenge. For centuries art historians has been struggling to reveal the real meaning behind the painting. Botticelli left his work unsigned and undated, leaving experts forever more to wonder about the painting and its meaning in history. There are many conflicting theories that has been evolved in Primavera, and there is no definitive answer, but only from historian’s hypotheses. At the very least, experts can all agree that the painting is sending a message about the assembly of gods enjoying the perpetual and joyful spring. No matter what kind of interpretation is given, Primavera will always a beautiful and fascinating painting.

Paper written by Nigel Feng for Renaissance Art Course at NYU-London

Works Cited

Cunningham, Lawrence S.; John J. Reich (16 January 2009). Culture & Values, Volume II: A Survey of the Humanities with Readings. Cengage Learning.

Dempsy, Charles. “Botticelli’s Three Graces.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. Vol. 34. Warburg Institute, 1971. 326-30. Print.

Dempsy, Charles. “Mercurius Ver: The Sources of Botticelli’s Primavera.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. Vol. 31. Warburg Institute, 1968. 251-73. Print.

Emil Jacobsen, Allegoria della Primavera di Sandro anno III, fasc. V, 1897, pp. 321-340. Botticelli, Archivio storico dell’arte, 2nd series.

Horace, Odes, I, 30

Ibid., p. 103

Lucretius, De rerum natura, v, 737-40

Levi, D’Ancona Mirella. Botticelli’s Primavera: a Botanical Interpretation including Astrology, Alchemy, and the Medici. Firenze: L.S. Olschki, 1983. Print.

Lightbown, Ronald. Sandro Botticelli. London: Paul Elek, 1978. Print.

Streener, A. Botticelli. London: George Bell and Sons, 1907. Print.

Zirpolo, Lilian. “Botticelli’s “Primavera”: A Lesson for the Bride.” Woman’s Art Journal. 2nd ed. Vol. 12. Woman’s Art. 24-28. Print.

SOURCE:

http://nigelfeng.wordpress.com/2012/03/28/la-primavera-an-analysis/

This is my Christmas gift and the book I`m reading now:

THE EMERALD GAME

by Culianu and Wiesner

This is an article about the book. Sorry, I couldn`t find the notes.

“Christmas is built upon a beautiful and intentional paradox; that the birth of the homeless should be celebrated in every home.”

― G.K. Chesterton, Brave New Family: G.K. Chesterton on Men and Women, Children, Sex, Divorce, Marriage and the Family

“What kind of Christmas present would Jesus ask Santa for?”

― Salman Rushdie, Fury

“And so this is Christmas...what have you done?”

― John Lennon

A Christmas candle is a lovely thing;

It makes no noise at all,

But softly gives itself away.

~Eva Logue

Era un tumult în ea, care-i lega sufletul dragostei de sufletul copilăriei din noaptea Crăciunului. Aceeaşi atingere de taină, aceeaşi depăşire a obişnuitului sufletesc, acelaşi contur de mirări, ş-acelasi monolog care simplifică sufletul, dându-i o intensitate de clopot care sună, amplificându-se prin unda muzicală. Atunci spunea mereu, cu dinţi de lapte: A venit Moş Crăciun! A venit Moş Crăciun! Şi era mică printre jucării. Acum gândul femeii spunea: Sunt cu el! Sunt cu el! Şi era fericită până la nelinişte şi spaimă: ş-atunci, ş-acum.

Ionel Teodoreanu în Tudor Ceaur Alcaz

Fifth Holy Sonnet

I am a little world made cunningly

Of Elements, and an Angelike spright,

But black sinne hath betraid to endlesse night

My worlds both parts, and (oh) both parts must die.

You which beyond that heaven which was most high

Have found new sphears, and of new lands can write,

Powre new seas in mine eyes, that so I might

Drowne my world with my weeping earnestly,

Or wash it if it must be drown'd no more;

But oh it must be burnt! alas the fire

Of lust and envie have burnt it heretofore,

And made it fouler; Let their flames retire,

And burne me o Lord, with a fiery zeale

Of thee and thy house, which doth in eating heale.

COMMENTS

-

Halee

08:45 Dec 31 2012

Shakespear good taste