← Mentorships

John Hunyadi (Medieval Latin: Ioannes Corvinus; Hungarian: Hunyadi János; Romanian: Iancu or Ioan de Hunedoara) (c. 1387 – August 11, 1456), nicknamed the White Knight, was a Voivode (Ruler) of Transylvania (from 1441), captain-general (1444–1446) and regent (1446–1453) of the Kingdom of Hungary, with a distinguished military career and father of Matias Corvinus (one of the most renowned kings of the country). John Hunyadi is considered a defender of Christendom for inflicting several defeats on the Ottomans including at Nis (1443) and for halting their advance into Europe, at least until seventy years or so after his death. Pope Calixtus III declared him an 'Athlete of Christ'.

Facing what was at the time the only standing army in Europe, the Janissary corps, he established his own regular army, which served as a model for others in Europe. His emphasis on tactics and strategy instead of over-reliance on frontal assaults and mêlées represented a significant contribution to military science. After a final victory against the Turks from July 21-22, 1456, during the Siege of Belgrade, he caught the plague and died. John Hunyadi has hero status in the national discourse of Romania and Hungary. Hunyadi's role, significant for the whole of Europe, lifted him from the local and even from the regional into the context of the whole of European civilization, to which he belongs as much as he does to any single national tradition.

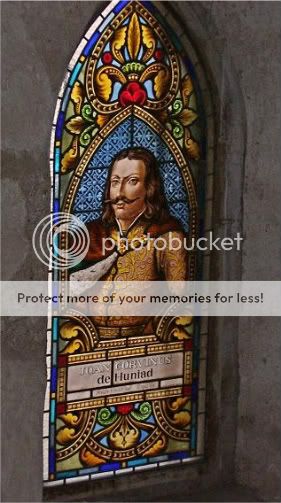

~ Iancu in his armor ~

The Chronicle of Johannes de Thurocz - 1499

Early career

Iancu of Hunedoara is first mentioned, probably as a small child, in the diplomas by which King Sigismund transferred possessions of Huniade castle (now at Hunedoara, Romania) to one of his knights, Woyk (or Vajk), who was Huniade’s father. Iancu was of Walachian (a region now in Romania) ancestry.[1]

According to the usage of Hungarian noblemen of the time, Iancu took his family name after his landed estate. The royal donation had elevated the Huniade family to the top ranks of the lesser (nonbaronial) group of Hungarian nobility. Proprietors of a domain containing 40 villages, they were considered as well-to-do as but ranked far below the great magnates who formed the king’s council and exercised the real power in the country.

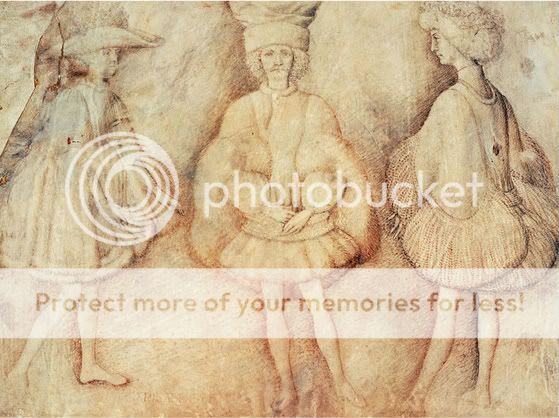

~ Pisanello (Antonio di Puccio): Three men in court attire ~

1431—1433; London, The Trustees of the British Museum, Department of Prints and Drawings

Young Iancu followed the normal career of his class. As a knight leading troops of up to 12 mounted warriors, he offered his services to more influential members of the ruling class. Through the influence of Stephan Lazarević, prince of the northern Serbs, and Philippo Scolari, one of Sigismund’s best soldiers, Huniade found his way to the royal court. Soon after, he married Erzsébet Szilágyi, daughter of a nobleman who had distinguished himself in military actions along the borders. The young knight accompanied the King to Italy and other foreign countries. In Milan he made the acquaintance of the condottiere (mercenary captain) Francesco Sforza and studied the new military art of Italy; he later studied the techniques of warfare developed by the Hussite insurgents in Bohemia.

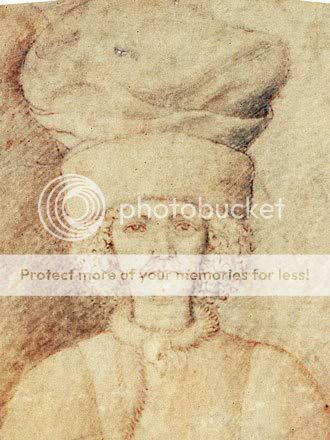

~ Detail - portrait that probably represents Iancu ~

The Rise

On his return home, Huniade was considered the best warrior in southern Hungary. He was still without high office, but he commanded 50 to 100 armed men against the increasing wave of Turkish attacks. His victories, though of local importance, attracted wide notice. With Ottoman troops occupying Serbia in 1439, the peril of a direct invasion of Hungary became imminent. Thus, Hunyadi was appointed bán (military governor) of Severin (now in Romania), a district exposed to continual attacks. His success in this command brought him rapid advancement and higher honours, including gifts of landed properties and other income. He was made voivode (governor) of Transylvania, count of Temes (now Timiş, Rom.), captain of Belgrade, and military leader of the whole defense system on the southern borders. He soon reached and surpassed the level of the wealthiest old baronial families. In the years that followed, he was able to repel the Turks not only from the borderlands of Hungary but from neighbouring Walachia as well.

After the death of the Habsburg German king Albert II, who, as Sigismund’s son-in-law, also was the king of Hungary, Huniade supported the election of the young Polish king Władysław III (Ulászló I in Hungary) in the hope of active and powerful support for a crusade against the Turks.

~ Main Castle of Iancu near Hunedoara during the night ~

The Victory

The “Long Campaign.” The famous “Long Campaign” took place in the autumn and winter of 1443–44. The preparations needed time. Internal troubles in Hungary and the hostility of the Habsburgs were mollified with papal help. Venice and the papacy supported Huniade’s army financially and diplomatically. Poland and other neighbouring countries sent troops, and in Hungary the King levied an “extraordinary” tax for the crusade. Huniade himself recruited some 10,000 to 12,000 well-trained soldiers, including Czech veterans of the Hussite wars. Huniade recognized the inefficiency and unreliability of feudal levies and was one of the first European commanders to employ a regular army on a large scale. The whole army, after having penetrated into Serbian territories under Turkish occupation, reached a total in excess of 30,000 men. The combined forces crossed the Danube in October and occupied Niš (now in Serbia), Sofia (now in Bulgaria), and some fortified Turkish garrisons. Huniade’s troops, advancing ahead of the rest of the army, prevented the Turks from unifying their forces and dispersed them in a series of battles. The crusader force reached the Balkan Mountains in December, but frost and difficulties of supply forced its retreat. They returned to Buda at the beginning of February, having broken the Sultan’s power in Bosnia, Hercegovina, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Albania.

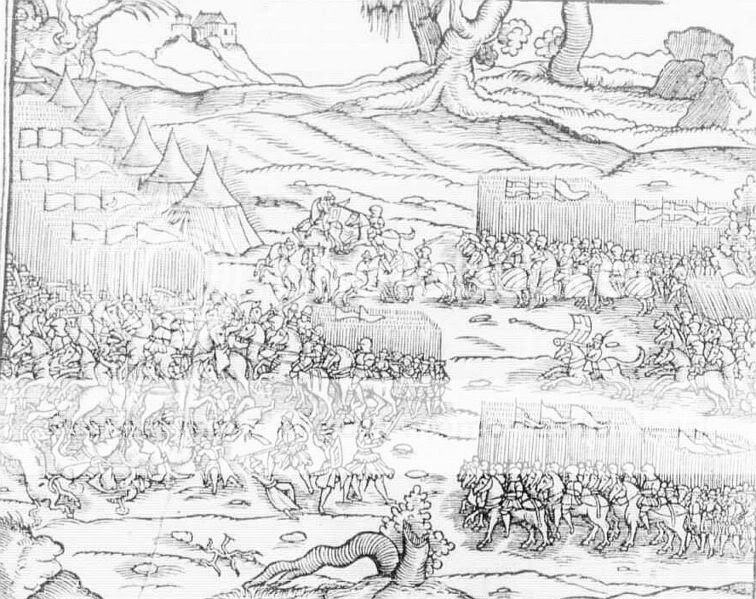

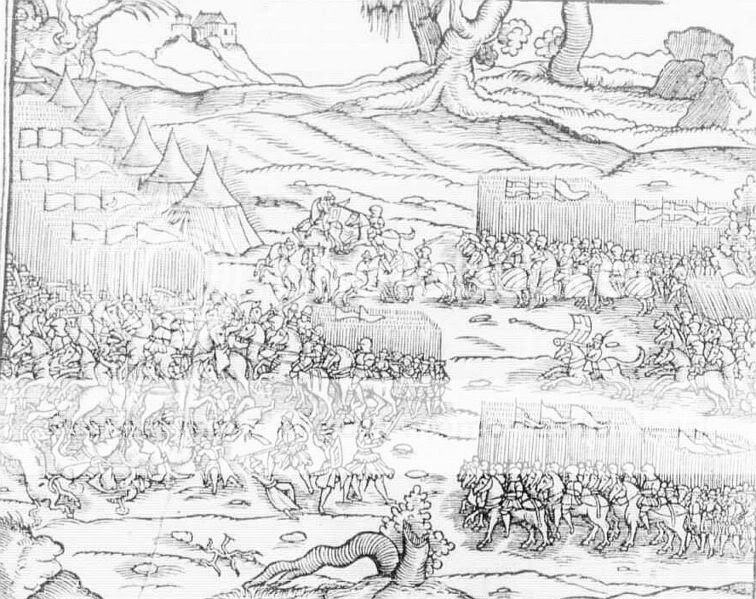

~ The battle of Varna 1444 ~

Martin Bielski's Polish Chronicle, 1564

The Disaster

The success of the campaign was unprecedented in the history of Turkish wars in Europe and evoked great enthusiasm in the Christian world. Sultan Murad II sued for peace. A 10-year truce was concluded but was broken when it was learned that a Venetian fleet was sailing to the Dardanelles to prevent the Sultan from recrossing into Europe. In July the Hungarian army went on the offensive to drive the remaining Ottoman forces from Europe. When the Venetian fleet failed to reach the Dardanelles, however, the Sultan crossed over with a large army and overwhelmed the outnumbered Christian forces at Varna on Nov. 10, 1444. Although Hunyadi’s troops were able to disperse the Turkish cavalry, King Ulászló’s attack on the Sultan’s camp miscarried. The King was killed, and Hunyadi narrowly escaped.

~ Stained glass with the image of Iancu ~

Governor of Hungary

The renewal of feudal anarchy in Hungary after the death of Ulászló demanded exceptional measures, and in 1446 Hunyadi was elected to rule the country as a governor during the minority of the young king Ladislas Posthumus (László V in Hungary). Hampered internally by the jealousy of the magnates and harassed externally by Emperor Frederick III, Huniade nevertheless restored order and tried to reorganize the economic, political, and military base of the country for a counterattack against the Turks. In 1448, before he could make contact with his Albanian allies, he met the Turkish army at Kosovo, where he lost a hard-fought battle. After that defeat his influence in Hungary waned, though he remained captain general of the kingdom with the right to administer royal incomes. He was unable to launch a counterattack against the Turks and could not go to the aid of Constantinople during the Turkish onslaught in 1453. A few years later, Sultan Mehmed II, conqueror of Constantinople, mounted a new offensive and in 1456 laid siege to Belgrade. Huniade provisioned and armed the fortress of that city, collected a considerable army of mercenaries, and was joined by a poorly equipped and ragged army of peasants. This untrained army, with the aid of Huniade’s troops, won one of the most remarkable victories in the history of Turkish wars, on July 22, 1456. Not only was the siege raised, but the relieving forces actually made sorties into the enemy camp. A few days later Huniade died of an epidemic that had broken out among the troops. The military success remained unexploited, though not without consequences; Hungary was saved from Ottoman conquest for 70 years.

Though he never realized the dream of contemporary humanists of driving the Turks from Europe, Huniade earned a glorious name by his considerable successes and by the mere fact that he succeeded in stopping the supposedly invincible Turkish armies: hence, his characterization in contemporary sources, “the only fear of Turks” or—with an expression of Turkish origin—“war’s lightning and thunderbolt”—an appraisal rarely granted by Turkish warriors even to their own leaders. His younger son became king of Hungary in 1458 as Matthias I.

NOTE: The only thing that links the Transilvanian Voivode to the vampire myth is the novel written by Paul Feval in 1860 named "Knightshade" ("Le Chevalier Ténèbre"in original - French).

~ The guarding gisant from his tombstone ~

NOTES

[1] The Walachian name of his father seem to be Voicu de Hunedoara or Huniade, but in the Hungarian chronicles all the names have a Hungarian translation as the Hungarians have a special prononciation of the words.The original name of the voivode seem to be Iancu(or Ioan) de Hunedoara, son of Voicu.

All his official acts are signed with the Latin name version of the name: Iohannes Huniady

[2]Pisanello (Antonio di Puccio): Three men in court attire

1431—1433; London, The Trustees of the British Museum, Department of Prints and Drawings

The three men probably belonged to Sigismund’s retinue during his tour of Italy (1431-1433) for his coronation as Holy Roman Emperor. The splendidly-dressed figures are certainly persons of the court, and their clothes are strongly reminiscent of those on the Emperor’s retinue as depicted on a relief of the coronation on the bronze gate of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Attempts have been made to identify them: from the ivy wreath on his head, the figure on the right may be the court poet, and the moustache — fashionable only in Central Europe at that time — and curled hair of the central figure possibly marks him out as Iancu Huniade, a member of the imperial retinue. Although there is nothing to disprove these hypotheses, it is more likely that Pisanello’s intention was to depict certain — and to him strange — types of apparel worn by courtiers accompanying Sigismund.

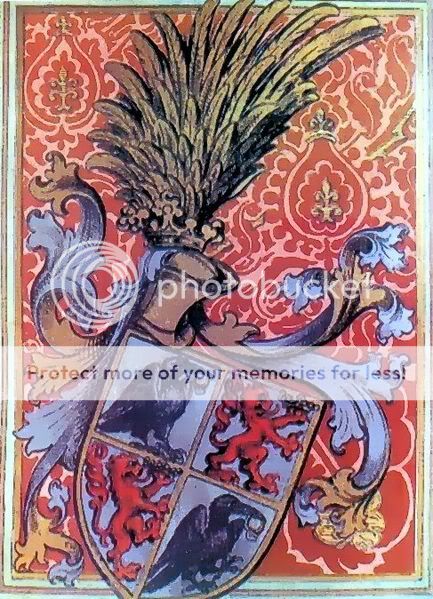

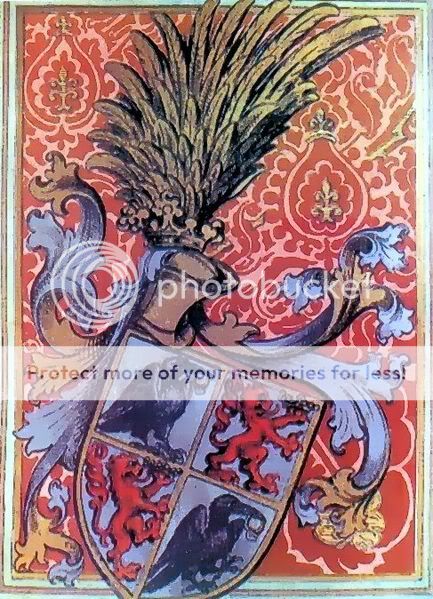

~ the coat of arms of Corvinus Family:

two black ravens(the origin of the name Corvinus)

and two red lions on azure ~

Sources:

http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/John_Hunyadi

http://www.medievistica.ro/texte/istorie/cercetarea/heraldica/heraldica.htm

http://oasteamica.forumbook.ru/personaliti-f1/iancu-de-hunedoara-imagini-t12.htm

RECENT FORUM POSTS

Sire (100)

Locations A to Z

00:37 - February 11 2026

READ POST

Superior Sire (148)

Four Word Story

17:29 - February 15 2026

READ POST

Venerable Sire (134)

REAL VAMPIRES LOVE VAMPIRE RAVE

Vampire Rave is a member of

Page generated in 0.0372 seconds.